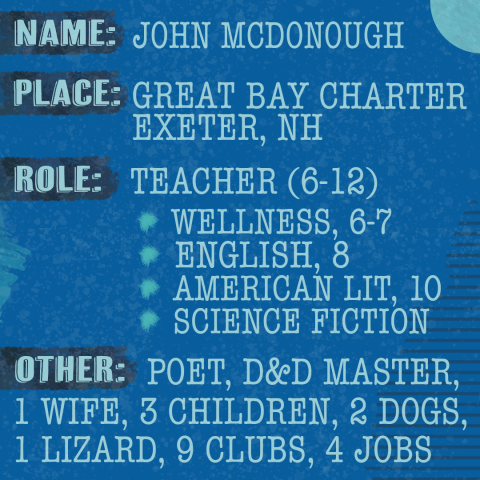

Where do you teach?

Great Bay Charter School in Exeter, New Hampshire.

Which grades or subjects do you teach?

I teach 6-12 grade. A high school science fiction class, a tenth-grade American literature class, an eighth-grade English Language Arts class, a Wellness class with sixth and seventh graders, and then Advisory, which is more like a check-in on non-academic things. You know, the stuff that goes into being human.

What are your mornings like between 5am-9am?

I usually wake up at 4:30 or maybe 5:00 to get a workout in. I’m neurodivergent. I went to the school that I teach at now, and that’s the population that we serve. I face a lot of the same challenges as my students. So I have to lift weights or run or do some yoga—something to get the first round of wiggles out.

Then I wake up my kids around 5:30 and help my wife get them ready for daycare. I have to get out of the house by 6:30, so I’ll do things like cook breakfast and get the kids dressed. I really like picking out their clothes. I walk the dogs, feed the dogs, feed the children. Then I’m out the door. And if I’m lucky I’ll remember to eat something myself.

I drive about an hour to school, and that’s when we start Advisory. At my school we all start in the cafeteria together and have a chance to check in with our students, see if anybody’s having a bad day. Usually, I catch that pretty fast. I have a really good, almost cult-like relationship with my advisory. It’s kind of like Harry Potter. They really do try to match the personalities of the advisors and advisees, and I have all the really energetic boys who can’t sit still and one girl who is super into dinosaurs, just like me. Her goal is to be a paleoartist when she grows up.

What’s a paleoartist?

Paleontologists have all these ideas, right? Let's take the Spinosaurus. Spinosaurus Aegyptiacus. I love the Spinosaurus. It’s this big dinosaur that has a sail, a big long snout, a big long tail, and it's hard to find.

When the Germans invaded North Africa—one of the things that the Germans love to do is get all their scientists in a new place and start digging for relics. So they get all these German paleontologists and archaeologists and find a Spinosaurus, the very first one, and sent it to a museum in Berlin. And then guess what happens to Berlin? Yea, the city mostly gets flat. And we lose our Spinosaurus, and now we're just relying on scientists talking about a fossil that used to exist and how they think it might fit into a bigger picture, right? But you can’t expect a paleontologist to draw anything past a stick figure, so they need to be able to sit and chat with a paleoartist who is able to capture what a Spinosaurus used to look like.

We used to think that the Spinosaurus stood straight up, had little tiny arms like a T-rex, dragged its tail on the ground. Now we know that it was completely aquatic, way closer to a crocodile than we ever would have imagined. But every time we realize—oh, the hip actually faces like this, the coloring needs to be like this, we need a paleoartist to interpret it. Part scientist, part artist. They need to be really informed.

So now my room is full of murals. Big murals. I just let this advisory student go to town on my walls. We have a big Edmontosaurus in one corner. We have Pepsi the Cassowary in another. Cassowaries are big birds. But birds are dinosaurs. That's one of my foundational principles. I feel like if you can understand the fact that birds are dinosaurs, that’s the most important thing a human being can learn, right? Because it unlocks everything. There is this knowledge, and for a whole host of reasons people don’t want you to know it. The church would like to actively dispel the idea that birds are dinosaurs. It complicates the idea of like extinction. It complicates so many people's narratives that we just ignore it. Because if an alien came to Earth and was like, tell me about Earth, you’d go, well, there have been these dinosaurs running around for hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of billions of years. And then like 500,000 years ago, these weird monkeys showed up.

Whose story are we? We, as a race, have main character syndrome. The story of Earth is a story of birds. It's like, I’m sorry the rest of Queen, but Bohemian Rhapsody's not about you.

What happens after Advisory?

During first period, I check in again. I know that we're supposed to be doing that during morning meeting, but I'll reserve five or ten minutes to ask what’s going on. It’s the same with coworkers. If somebody walked up to me like I was a video game character and started launching into my mission, I would get pissy with them. You're not going to ask me how I am? You're not going to ask me what I did last night or how my weekend was? I make a point to talk to each of my students. And I make a point to tell them about me. Oh, Hooper did this thing. The other day I got a lot of miles with a story of how Elizabeth fell into one of Penelope’s dirty diapers. That’s a good one. So I try to tell them a little bit about me and have them tell me a little bit about themselves. We do block scheduling, so then it’s off to the races.

My first class is either Science Fiction—and I mean, that’s always a great way to start the day. The other class I start with is Wellness. And with those guys I try and get movement in first thing for the same reason I use movement to start my day. Because before we do anything, we have to get in a good space for it. Sometimes we'll do yoga, sometimes play a game of basketball, sometimes we'll jump ropes.

I really like to use my classroom. I keep fun noodles in my room and a beach ball. And if I notice kids are getting fidgety, I'll stop everything and we'll get the foam noodles out. And we’ll play this version of hockey that I think I might have invented. I saw noodles on sale once, and I was like, I bet I could use those for something. And they sat in the corner of my room for six months until I realized—those are hockey sticks. Like, that's what those are. So we play hockey in my room, stuff like that. Just try and get the kids moving and sweating.

Because I think that everybody should sweat and get emotional at least once a day. Whether it's really happy or really sad or really angry. In general, you're leading a pretty good life if every day you sweat and every day you get emotional. So I try and curate that for my students.

What’s one lesson you’re proud of?

I don't know if you're familiar with the Battle of Thermopylae. It’s this really interesting battle from ancient history which kind of created the idea of Western civilization. Because the Persian empire came to invade mainland Europe, specifically Greece. And there were all these Greek city states who were like, hey, we don't really feel like being part of the Persian Empire, so we're going to resist. And that's when the Greek city states had to coalesce for the first time into one big unit.

One of the major battles of that conflict was at Thermopylae. Sparta had sent one of its two kings there during a big religious festival. And technically, the Greeks weren't allowed to engage in warfare during the holiday, which is why the Persians chose to invade then. Because Sparta was known for being really good at poking people with sticks. So the Persians thought, we should do this while Sparta is, you know, on Christmas break.

And the king is sitting around—his name’s Leonidas—and he's going, “What if I just took a hike and brought my personal bodyguards with me? And if I run into the Persians, I run into the Persians? It shan’t be my fault.” But he can only bring so many dudes. So he brought 300 guys to fight, while Herodotus reports that there were about one million Persians.

So there's this spot in Greece called the Hot Gates. And King Leonidas goes off on his nice sightseeing tour of the Hot Gates, which is a small straight in Greece that's buffeted on one side by the ocean and on the other side by big cliff faces. It's all about force multipliers, which is what they call it in military speak. The idea is that there were only 300 Spartans, but they had all these force multipliers. There were more Persians, but they all had to go through one very narrow pass.

The lesson I came up with to explain force multipliers was a game of dodgeball. The Greeks were known for having heavy armor and using these force multipliers. And the Persians had light armor but just endless amounts of Persians to throw at them. So my eighth graders were the Spartans. They made their own armor and everyone dressed up in cardboard shields and helmets and things like that. And then I took the rest of lower school and said, you're the Persians.

We kept it to three eighth graders against the entire rest of the school. But we set it up just like the Hot Gates, with a wall on one side and a very narrow area that all the kids had to funnel through. Sure enough, we did it like ten times and the Persians never made it.

And in Thermopylae, what wound up happening was the Spartans held their spot for three days, and then the Persians finally paid somebody to tell them about a way around. So when the lower grades were frustrated and giving up, that’s when I said, “all right, what if I told you that you could go all the way around the school and come up behind them?” Then all of a sudden, the eighth graders lost their advantage because the lower grades outflanked them.

I thought that was a real—I mean, that’s a lesson everybody still talks about today. I’m proud of that one. Dodgeball Thermopylae.

What’s your favorite book to teach?

My favorite book to teach is Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs? It's by this woman, Caitlin Doughty, who is a mortician. She's written a few books, but in this one each chapter is a different question that she's gotten from a kid about death.

And so, like, will a cat eat your eyeball? Oh, yes, cats will eat your eyeballs. You will die and your cat will almost immediately start munching.

And so, like, will a cat eat your eyeball? Oh, yes, cats will eat your eyeballs. You will die and your cat will almost immediately start munching. But the book goes on to talk about dogs as well. And that’s fascinating to me because there may be some injurious behavior after you die from your dog, but it's almost always because your dog is trying to wake you up. That's the difference between cats and dogs. The second you drop, the cat’s like—food! The cat will eat its own grub until it runs out, but it’s not going to skip a meal for you. It’s like, mom's not getting any better. And dogs, it probably depends on the dog when and if they start in.

But there are all sorts of thought-provoking questions that work for almost any age group. Like everything from, can I turn like my parents into something cool after they die? If I want a mom-based paper weight or something, can I do that? I think it forces kids to interrogate why we do things the way we do. And so much about the death industry is just—well, we’ve done it that way, so we're going to continue to do it that way.

There was once a very real purpose for these things. Embalming started in the Civil War because so many people, for the first time in American history, were dying so far from home. But we could reasonably identify them when they were dead. We could figure out where they were supposed to go, but the obstacle was getting them there before they decayed. So they came up with an idea, a good idea, for getting these guys home. But then it became an industry, right? It became profitable and the Civil War ended. But all those people making money off embalming didn't want to stop making money.

In a weird way, there are so many parallels between the death industry and education. And the book gets students to start thinking about why things are the way they are. I mean, if you're thinking about death, you’re inherently thinking about life.

What’s a movie you like to teach?

I teach Godzilla a lot. And this year I’m doing Godzilla with my science fiction class. It's a fascinating movie because it's got a really low cost of entry. Anybody can sit down and enjoy Godzilla. My newborn sits there and watches monsters tee off on each other, and she enjoys it. But when you look at it through the lens of history—I mean, this was a movie that was made nine years after civilization withstood two atomic weapons. The first and only time in history that atomic warfare has been used on civilian populations.

But the United States government was still dictating what they could publish in Japan at that time. Godzilla started off in Toho Studios as a documentary about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but the United States government was like—no, you're not. And they had to figure it out: how do we talk about the thing without talking about the thing? So you have this big monster that comes out of the West and totally decimates cities.

Most Americans have seen the ’56 Godzilla that they put out in English with American actors and dubbed over. But the 1954 picture is so powerful. I like teaching it because it opens kids’ eyes to the fact that you have this whole history that's been curated for you by very powerful people. Students invariably start off thinking of Godzilla as this goofy monster that does goofy stuff, and he is very much that. But there's also this other thing that you can take from the buffet.

So four or five years ago I made friends with this guy, Dr. William Tsutsui, who happens to be the lead expert on Godzilla in the world. He's a professor of Japanese studies. He's the chancellor of a university. And he comes and visits every year whenever I do Godzilla now. He’s a really cool guy with a cool story, because for most of his life he was told no. There’s no space for you here. There’s no room. And he found a way to just keep doing it. He didn’t take no, and finally academia had to make a spot at the table. And he wrote a book called Godzilla on my Mind that talks about his experience as a Japanese American kid, and how the first time he felt cool was when Godzilla came out. And all the sudden, Americans were like—there’s a thing from Japan that came out that I like. Which also shows the power of pop culture, which I think is just culture. You know? That's one of one of my things. Like there's no difference between Hamlet and Wonder Woman.

That's one of one of my things. Like there's no difference between Hamlet and Wonder Woman.

Have you ever gotten push-back?

I'll tell you a story. Every year we do summer reading, and when I got hired, the first thing they did was ask me to pick a book. They said, whoever signs up for your book is going to read it over the summer. The first thing you'll do when you come in is meet with your book group students for the first week.

And I was like, okay, what do kids read in middle school? I sent in—I don't even remember what I sent. It probably like, Johnny Tremain, The Outsiders, whatever. And our Assistant Director sent me a text. She said, John, what are these books? And I said, you know, summer reading? Things that middle schoolers read? And she said, to be perfectly frank, if we wanted Johnny Tremain, we would have hired the other guy. We hired you because you have all these things that light you up.

And that year I wound up teaching Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, which is a comic book that I absolutely fell in love with. A girl becomes from with a satanic dinosaur and they have all these adventures together. So yeah, I would say I don't really get a ton of pushback. I think more often than not, I will get comments like, okay, whatever you want to teach is fine. Can you make sure you're getting in this thing? Or, test scores have been really low on that. Can you use your thing to teach this thing? How does Godzilla intersect with the five paragraphs? That can be a bummer. But for the most part, there’s freedom. I don't think I could walk into a lot of schools and be say, here's my semester-long Godzilla curriculum. It’s going to take half the year. You're going to love it.

Okay. A few rapid-fire questions. Who are two people living today who you admire professionally?

The first one that comes to my mind is Cornel West. Cornel West is an academic. He's a philosopher, but he's just got this great energy. Even people he reviles, he calls brother. Which I think is terrific. Right now, one of the things he’s doing is running for President. He’ll talk about Trump and say, “I think brother Trump is wrong.” Even though he’s been a civil rights maverick for so long and disagrees with these people fundamentally, he calls them brother.

And the other person I admire is a janitor that works in my school, Shannon. She's phenomenal. She's just the best—maybe the best person at her job that I’ve ever met. She and Edie, the other custodian in the school, keep our school running in so many ways. They’re incredible, Shannon’s incredible. There’s just no other way to put it. I really admire her.

What surprised you most about becoming an adult?

What surprised me most about becoming an adult is how similar it is to being a child. It’s just the same. There’s such little differentiation. There are huge consequences, but there are huge consequences when you're a kid, too. There’s just so much sameness. We are just big children.

Even this morning, I went to a professional development session in Maine. We went outside and took a break and everybody broke up just like a bunch of sixth graders would. There were some people over in the corner on their phones. There were some people that were congenial and chatting with one another. There was somebody that went to go see if they could break the ice with their foot in the parking lot. And I knew all of them—they are my students.

Where were you?

Believe it or not, I was standing by myself and hoping somebody would come talk to me. I was hyper self-conscious because I was five minutes late when my GPS took me in the wrong place. So I was like, I'm going to become a wallflower. And that’s totally what I would have done when I was a kid if something happened and I was feeling self-conscious.

What’s one thing you’re good at and you never want to do again?

Being there when somebody gets birth. Yeah. I think I'm phenomenal at that. I'm really, really good, and I never want to do it again. My wife and I are done. I don't want to be there for somebody else. But I curate the play list and know what drinks to get and which post-birth meal to deliver. And I get out of the way when I need to, which is maybe the most important thing. I think I’m pretty good at cracking a joke. And I didn’t expect it, but I love it and am good at it. And I never want to do it again.

Thinking back over your last five years teaching, what’s a moment that stands out?

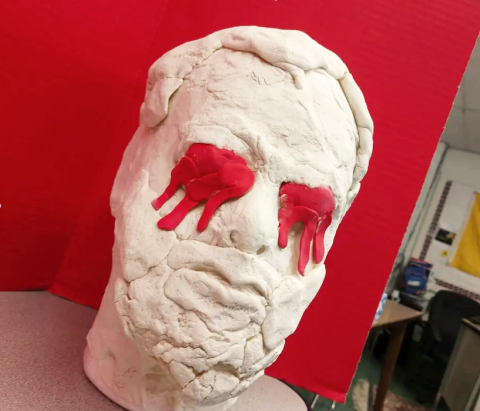

My first year I taught sixth grade and I had them read Oedipus. Yea, I had a lot to learn. But that year I taught Oedipus, and surprisingly my students really liked it. That was one of the moments when I got some pushback. I mean, Oedipus is kind of known for the one thing, but he's a really interesting character and there's all sorts of interesting parts of the story. And all semester everybody was telling me that they’re not going to get anything out of it.

But then it was time for Student Exhibition. And that semester it was a little bit more free form. The topic was, “what was something that got you really excited this year?” Do a project about that thing. And we ended up having a whole Oedipus room. For one project, a student did a stone bust of Oedipus after he got his eyes gauged out. He’s bleeding, he’s got hairpins sticking out of his eyeballs, and it’s right in the center of the room as parents and students roam around. And everybody loved it. It’s still in the school. The kids still love it. Everybody calls it Headoepus.

Those are the kind of stories I think about when somebody tells me that I’m not going to be successful. Hey, you remember Headoepus?

If you could make one change in education, what would it be?

This is going to sound self-serving, but I 100% believe that most of the problems in education could be solved by paying teachers more money. First of all, there's like this class-based system amongst educators right now in terms of just—when did you get into education? Because we have all these baby boomers that got into it when life was good. And they have vacation homes and extra cars and go to Europe. And then your younger teachers are working three or four jobs, they've got roommates, that sort of thing. I've got three kids, and being a public school teacher with three kids, just from a financial perspective, is wildly difficult. I work a bunch of extra jobs, and there's just no way to avoid it. And I know I’m a worse educator because of it.

But if you were to pay teachers more, you would get so much more. Because it’s about attracting quality talent to the field. It’s too late for us, but it will alleviate some of the burden for people down the road. Because—I mean, we can’t keep going on like this. Right now, it’s: I just came home from my second job, it’s 7:15, the kids are going to bed, and what am I going to buy off Teachers Pay Teachers?

And students get it. They feel it. It’s like the difference between McDonald’s and a Michelin restaurant. At McDonald’s you have a bunch of people that know just enough to make a quarter pounder, but they're not personally invested in that thing. But if you have the talent, the people that can come up with something creative that lights them up, they're going to have more pride in that thing and the results are going to be better. And it all stems from the idea that people shouldn't have to martyr themselves to teach, you know. You shouldn’t have to martyr yourself to teach.

And it all stems from the idea that people shouldn't have to martyr themselves to teach, you know. You shouldn’t have to martyr yourself to teach.

What would you miss most if you changed professions?

What would I miss if I changed professions? I suppose it depends on what profession I switched to. I imagine that I would probably wind up working with animals in some way. I like taking care of things—people, animals. If it breathes, I want to leave it better than I found it. I'm no good with like plants. They don’t get me going. But when I can look into something's eyes—I would miss that if I was working in an office or something. And if I switched careers, I would seek that out somewhere else.

But I would worry that if I switched professions to something else that I wouldn’t be able to effect positive change. And I’m sure I would feel guilty. I'm sure that would happen. Just making space for people, making space for different people. I think there needs to be people out there building shelter for weirdos.