Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Vermont. It was weird. But my elementary school memories are really happy. They were actually doing a lot of advanced pedagogical thinking. Like this is rural Vermont in the '90s, but my middle school was project based. In the '90s, yeah. A wild choice. I don’t know how they got that to happen.

I loved my elementary school, but when I look back at my middle and high school years, I hated it. I just didn't like school in general. I think maybe I've always been a little different. Like anarchist. And it seemed like everyone always thought they knew more about me than I did, and nobody was actually asking me about me.

But I also felt like no one ever told me what I needed to do to succeed in school. Looking back, I can see, oh Olivia, if you had just known your teachers wanted this, you would've done it. But education just seemed so amorphous and inaccessible, and I genuinely couldn't conceptualize that my teachers wanted something specific. It seemed like it was never explained to me until I did it wrong. Then I would have this terrible grade, and it was just game over. Like why try?

Every proposition to fix grading just becomes traditional grading. Standards-based. Competency-based. In the end, people just equate the new systems to traditional grading structures, which begs the question of conscriptive education in general. But then that gets to the foundations of a democratic society. And that's a whole thing. But I really don't know. I have no idea why I had so much trouble accessing my education, because I should have been able to. I was a white, middle-class kid whose parents were college educated. By all rights, I had the tools, I just couldn’t wrap my brain around it. Like I can tell you the things that were wrong with my education growing up, but I can’t tell you how someone would have helped me.

I mean, how do you change it? How do you make conscriptive education work for everybody? You don't, you can't. It's all just a big experience, right?

What were your middle and high school years like?

So I almost failed out of high school because of trauma. And then I didn't fail out a high school because of no Child Left Behind. After high school I went to a state school right down the road from me, like literally 10 minutes away. And I was an English major because—well, basically I didn’t like anything else. But I knew I loved to read.

Do you remember Gregory's Supply? My God. It was an empire. It was this hardware company in South Burlington, and my dad was a salesman there. He’s always been a salesman. And one day he brought me home one of the first laptops on the market. They lasted for five minutes and then you had to plug them in, so they were basically just like a computer. But he brought one home for me, and I used to write little poems on this laptop. Man, I loved it. I loved to read and write.

People were weirdly invested in me being a writer. I don't know why, but even as a kid everyone always bought me journals and talked about me being a writer. And I would say: but I don’t like writing in journals. Why are you only buying me journals? And then I would be even less likely to write in them because I was mad that they were only giving me this one thing, only seeing this one part of me. It was a vicious cycle.

The same thing happened with teaching. When I went to college, everyone was like, oh, you’re an English major. You’re going to teach. That’s what English majors do. And I was like, f*ck you. I don't want to teach and I'm not going to teach. That didn’t last long.

What changed?

I took a creative writing class in college, and that’s where I met my mentor, Liz Powell. She’s an incredible person and poet, and she’s still in my life. I mean, she officiated my wedding. And back then she recruited me to work on the school lit mag, the Green Mountain Review. She made me Assistant Poetry Editor. And as I was nearing the end of my school career, she pulled me aside and said, “you have to go to grad school. You have to get a master’s in fine arts.” And I had no other plans. So I was like, I guess I’m going to get an MFA.

It was out of respect for Liz and also as a f*ck you to everyone who told me I wasn’t going to get a degree. Because when I was in high school, even my college counselor told me I didn’t have the skills to get a college degree. And I said: I have the skills, I just choose not to apply them here. But I know I can do it. That was really the great story of my life in public education. But I ended up getting a full ride to Wichita State University for my MFA in Poetry so long as I taught Composition & Rhetoric.

Teaching my first class was terrible. A kid laughed at me, and I was like, I'm never doing this again. This is horrible. I ended up doing it for three years, but it was always like wearing an outfit that was slightly too big. I felt a lot of pressure to teach at the college level, especially because I was so young. And a lot of my favorite teachers from college were lecturers. I learned so much just from listening to them talk for 90 minutes. I soaked it up. But I didn’t have that level of knowledge, and I was really hard on myself that I couldn’t do the same. I thought I was failing my students.

But even though teaching was uncomfortable, I did like it. I mean, there was something there that I loved. I liked the relationship building and watching students progress. And I decided that if I ever went back to school, or just in my career in general, that’s what I would focus on.

Did teaching get easier?

Teaching didn’t really get easier at Wichita State, but I got better at it. It just never felt comfortable. But I mean, I think teaching is always a little uncomfortable. Even when people say that they don’t get nervous teaching after all those years, I think they’re lying. Everyone has anxieties.

You have to get up in front of a room of people and say, I know better than you. I know more than you. But you're not supposed to know better than them. There's this weird tension now where you're not supposed to be an authority figure in the classroom—you're supposed to be a guide on the learning journey. Which is nice. Like it's a nice way to think about teaching. But also, you can't ignore the fact that you are an authority figure in the classroom. And no matter what happens, everything you do and every move you make, the kids will notice.

Like when I was teaching at Wichita State, I had my students write journal entries for the first five minutes of class. And this one day I hadn’t worn makeup. One of my students—I mean, she was very sweet, a good student. And she wrote a very compelling journal entry talking about the racial differences in makeup. She was African American, and she wrote about how growing up she didn’t see women wear makeup, how no one around her did, but how white women always wore so much and it made them seem more insecure than the Black women in her life.

It was compelling and thoughtful, but—I mean, I didn’t think anyone was going to notice that I didn’t wear makeup. It was one day! But when you’re teaching, your body is always up for scrutiny no matter how good you are. I think this is one reason people feel uncomfortable in the classroom, because it's a very embodied existence. And if your body deviates from the norm in any way, it is anxiety inducing. The students will notice.

I think this is one reason people feel uncomfortable in the classroom, because it's a very embodied existence. And if your body deviates from the norm in any way, it is anxiety inducing. The students will notice.

Do you think teaching is different for men and women?

Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I mean, women are basically treated like moms. If I'm not super nice and maternal, it's shocking for people. And men—well, I can’t really speak to it, but they have a hard time too. People will challenge their authority physically versus emotionally. Because the emotional labor you're expected to do as a female teacher is wild. And no matter how good you are, your authority is always up for debate.

Because the emotional labor you're expected to do as a female teacher is wild. And no matter how good you are, your authority is always up for debate.

Students will try to physically intimidate women. I had one kid bring muscle to a conference about a grade. Now granted, this was like an older man, but it was very clear in this instance that I was supposed to be intimidated. Honestly, he was very sweet. I'm sure he could have beat me up if he wanted to, but he didn't have the proclivity to do so. But that wasn’t so unusual during my time teaching in K-12. Whether physically or emotionally, I think women are more manipulated in the classroom. And the bottom line is: how much are you going to let that affect you? How much are you going to let that impact your assurance in your own knowledge?

What happened after you graduated from your MFA program?

After Wichita I came back to New Hampshire and tutored for two years with a private company. That was super rewarding. I really loved tutoring one-on-one. You get almost instantaneous results with tutoring, which I didn't really get with teaching. It was problematic, because only really wealthy Massachusetts families could afford it. There was always this class tension.

But I liked tutoring. It has a very unstable place in the pedagogical cycle because it's outside of it. There's a spot for tutoring, but it doesn’t really fit because not everyone can access tutoring or even wants to access it. Whether it's free or not, there's still the cost of your time. And not everyone has equal access to time. So it’s in a weird liminal space, but you have to design it as though everybody is going to use it.

I've always had a lot of issues with the class ethics of tutoring, but the experience working at a private tutoring agency got me a job coordinating a tutoring center at Dickinson State University in North Dakota. My husband John and I moved out there, and I worked at Dickinson for two years.

I enjoyed being creative with the tutoring center, designing the physical space and working so closely with student tutors. But it’s not a position that comes with a lot of respect from the greater academic community. It's not a position that fit neatly into other teaching opportunities, which I was interested in pursuing. It can be a hard place to effect change, and that was difficult for me. So there were positives and negatives.

We moved back to New Hampshire because my husband John got a teaching job. The plan was that I would stay at home with our first child, Elizabeth. But that wasn’t a good fit for me. I hated staying at home all the time. I wanted to work. I ended up getting a job as a paraeducator and teaching part time at the same school as John. And then after that I taught there full-time for 3.5 years.

What was it like being a para?

I don't think I was good at it. It’s such a weird position. There's no bar of what you should be doing and if you’re doing it right. The bar people set is how your student is doing in class, which is obviously problematic for a lot of reasons. Yeah, it was not a good experience. The kid that I paired with—they were lovely. I really enjoyed working with them, and we’re still in touch.

But paraeducators just kind of get blamed for everything, from admin to teachers to parents. There really isn’t anybody who won’t blame you for something. I remember sitting in an IEP meeting and the parents were upset about some part of the IEP and when and if it was going to be implemented. I don’t remember exactly what it was, but they decided that I was going to do the activity with the student. And I said—sure, I’ll do it with them. But then the activity kept getting canceled, and there was a weird feedback loop. Everyone was upset that the activity wasn’t happening, and I ended up getting blamed for something out of my control since I was the one in the middle. I had said I would do it with them and then couldn’t.

I mean, God bless paraeducators. There are people who make careers out of it and are truly outstanding, but I couldn’t do it. It’s not the worst job I’ve ever had, but it’s definitely up there.

I mean, God bless paraeducators.

What about teaching?

In some ways I think it was inevitable that I became a teacher and a writer. I mean, of course I was going to. Everyone else was so invested in it, so invested in me teaching and writing, so it was both nature and nurture. And I'm really bad at office jobs. I'm just not good at them, at being in one spot. At sitting at the computer and filing reports and loading the office dishwasher. So I don’t really know what else I would have done other than teaching. Maybe publishing? I guess?

But I was a really good K-12 teacher. In many ways it was an awesome job, and I was good at it. As a teacher, you’re not supposed to say that you’re good. They get mad. People tell me that I’m full of myself or too assertive, which is just coded sexist language. But I think about the Barbie speech, and I’m into it. I was a good teacher, and I never want to do it again.

I mean, all the things that make teaching K-12 unsustainable are things that I’m good at. Empathy, connecting with students, really seeing what makes them tick and afraid and alive. I like to think in broad strokes and come up with these connective tissues, and so much of teaching is about being able to improvise persuasively. You watch a TV show and you're like, oh, I can teach this with this. I can use this thing to make this other thing clearer.

I taught Humanities, which is history and English combined. You get to make these huge, sweeping, broad connections, and then watch as the kids carry them out. It's so great. They’re doing all the work and you're the one standing up and making these wild links, prodding now and again. My skill set was really made for teaching. And I didn’t have a great K-12 experience, so I was really committed to not having them experience the same things.

But it’s not sustainable. Like, you can’t save them all. You just can’t.

When did you decide to leave teaching K-12?

When I finished my MFA, which is technically a terminal degree, I said I'm never going back to school.

But after Covid, I was done working in K-12. It was such a mess. It’s still a mess, but I knew I didn’t want to be in that educational space anymore. But I also knew that if I wanted to go back to higher ed, I really needed to get a PhD. And by then I had two kids and another on the way, and I wanted a more flexible schedule. So I left teaching K-12 in June of last year and am now in the first year of a PhD program in Composition & Rhetoric at the University of New Hampshire.

My approach with Comp is very much like, who are you as a part of this larger conversation you're engaging in? Eventually, every student in every comp classroom is going to go out and produce in their field. So what does that mean for you? What are the things you need to know? And how can you think critically about academic power structures and what they mean for you and for your specialty? There are huge issues with higher education in this country. Comp is, I think, poised to address a lot of them. We touch every student that comes through a university. And I think the field needs to be thinking about how we can shift the narrative in higher education.

Are your students in New Hampshire different than in Kansas?

For sure. New Hampshire just has a smaller sample size. It’s one of the whitest states. We pull a lot from Massachusetts, which is one of the most educated states in the nation, one of the wealthiest states in the nation, and one of the most segregated states in the nation. When we go around the room and introduce ourselves, it's like, oh, I'm from Newton. Oh, I'm from Winthrop. Those are lovely communities, no shade, but many students, though not all, can afford to access education in a different way than other parts of the country. That's not a bad thing, it’s just different. And it means different things for the classroom.

At Wichita State, one time I ended up doing a whole class on Planned Parenthood. I didn't mean to. I didn’t lesson plan it out or anything, but one day we were workshopping a personal narrative essay. And a girl wrote about being a teen parent and going to Planned Parenthood for prenatal care.

For context, I actually went to Planned Parenthood in Kansas regularly for birth control. And it was literally behind bars. You had to get buzzed in. There was bulletproof glass everywhere. It was like going into a prison. There were constant bomb threats, fires. It was not a safe place to go. Like, I don't know if you've ever been to Planned Parenthood in New England, but they’re lovely. It’s like you’re walking into an antique house and everything is cozy and quiet.

The students were super nice about this essay. I remember that class so well. I loved them. And this one kid was said, okay, I really like this essay, but I don't understand why you went to Planned Parenthood? Because Planned Parenthood is for abortions, so were you trying to abort the baby?

I was being observed that day, but I had to stop the class. I said, “that’s a valid question. You’re not in trouble, but here are the things that Planned Parenthood does. And it's important that you know this because you could go get screened for STD's. You can go get free condoms.” And it just snowballed from there with other students asking—do they do this? Do they do that? And they just didn't know. They didn't know. Nobody had ever taught them about sexual health or wellness. Is the Comp classroom the place to do that? No, no it’s not. I’m not a sex educator, but also, who else was going to?

I was so worried the whole time that I was going to fail my teaching observation. But luckily, the woman observing me got really excited. She said that it was the right thing for me to do, and she really affirmed my decision. That was a pretty formative moment for me as an educator because I thought that the conversation was important and someone else in power thought so, too.

I don't think that I would have a moment like that at UNH. The students are bright and thoughtful, just like my students in Wichita, but we have different conversations. At UNH I focus more on dismantling power structures in a larger sense, whereas in Wichita it was more talking about things like Planned Parenthood and asking, “what could it do for you?” That’s also dismantling a power structure, just on a smaller scale.

What’s it like teaching college students as opposed to middle schoolers?

Middle schoolers are so much more fun. They still want to explore and do fun things. I mean, when I was teaching K-12 I had a kid bring his pet lizard to class. Each student had to design a project and present, and he did a whole thing on this bearded dragon. He brought it to class and demonstrated how to take care of it and clean the tank. It was so cute, so informative.

College students are fairly flexible, but I think they’re more concerned with the bolts and brass tax. If it’s fun, they almost don’t take it seriously. It’s devalued. But it’s tough because you have to keep their attention, so you’re constantly walking this fine line between, “I want to keep your attention, but I can't be too fun. Because if I'm too fun, then you won't take this seriously.” Whereas in middle school, if you bring in a bag of candy, it's just like, this is the best day ever. Everyone's happy.

Did anything surprise you about becoming an adult?

I think it’s that I really don't feel like an adult. I'm 33 with three kids and a mortgage and—I don’t know if I can say career—but there’s something there, and yet I just don't feel like a grown up. When I was a kid, all the grown ups seemed like they really felt grown up. There was an assured quality. I don't I don't have that at all.

But something else that’s surprised me is how often people tell me to be quiet. As an adult, yeah. Who's still going to be quiet? But my God, so many people try to shut me up. It could just be that I talk too much, but this has happened so many times in so many different ways. Everywhere, almost every job I've had outside of being here at UNH, I have gotten in trouble for saying the things. It just seems like no matter who you are or where you are, if you’re challenging the status quo, people want you to stop talking. They just don’t want to hear about it.

Everywhere, almost every job I've had outside of being here at UNH, I have gotten in trouble for saying the things. It just seems like no matter who you are or where you are, if you’re challenging the status quo, people want you to stop talking. They just don’t want to hear about it.

Do you have any moments that stand out in your teaching career?

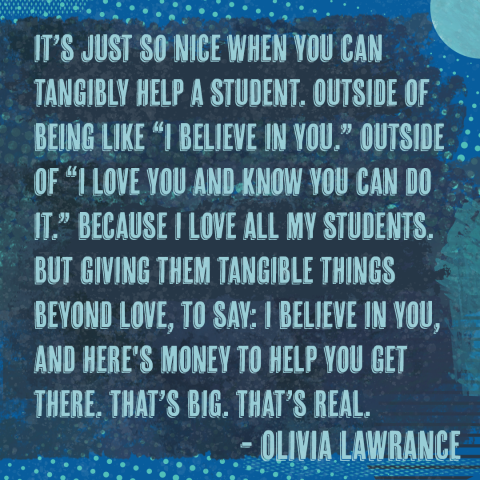

There are a few students that I’m really proud to have worked with. Like this one girl—I helped her get funding for Driver’s Ed. And those are the things as an educator that I really like doing—helping students apply for grants and things to give them more access. But that stuff is complicated. Dumping your trauma for a scholarship, right? It's give and take.

But I had a few students that I helped apply for this one scholarship fund. It’s so cool. Their mission is to give students access by funding their education wholly—certifications, beauty school, whatever. And this one girl, she was awesome. And in the middle of a creative writing class we started talking about college. I was sure this kid was college-bound. Absolutely sure of it. But during this one class I kind of casually asked who was thinking about college, and she said she wasn’t. And I was like, what do you mean you're not going to college? You have to go to college. You're brilliant, you’re an English major. The world needs you to do this thing.

I wasn’t trying to be a transcendental teacher or whatever. I was genuinely like, oh my God, why has nobody had ever told you this before? And nobody had. I don’t think it was shortcoming of anybody, it had just never come up. And this girl had decided a different trajectory, a perfectly valid one, but no one had ever asked—why not college? Why not this other thing?

These kind of interactions—I mean, they’re the kind of moments you hope for as an educator. They’re hard to talk about without seeming like you’re in the Freedom Writers. But it was really meaningful. I helped her access all these things that seemed beyond her reach, unimaginable really. We’re still in touch—we just went to a scholarship event together—but it’s just so nice when you can tangibly help a student. Outside of being like “I believe in you.” Outside of “I love you and know you can do it.” Because I love all my students. But giving them tangible things beyond love, to say: I believe in you, and here's money to help you get there. That’s big. That’s real.